Why did America Really go to the Moon?

Believe

it or not, it had very little to do with space or the moon --

it was actually a

matter of life or death which almost certainly saved the lives of millions.

Iceberg dead ahead: Kennedy addresses a Special Joint Session of Congress

To most people, especially those who are not

particularly interested in space flight and lament having to go out to work

every day to pay for it, the cost of projects like Apollo must seem extravagant

at best, and downright irresponsible at worst in a world where two billion are

undernourished if not starving, and are living their lives in poverty.

Further, it's nothing short of an act of political suicide for an elected

public servant such as an American politician to expect his voters to work to

pay for this, when his political opponents could relieve the burden he imposes

upon them by simply cancelling the project.

So why then did John F. Kennedy, who won his election only narrowly, order that America go to the moon?

The answer to this is actually rather serious -- far more serious than space or the moon -- but is consistently missed by just about everyone who thinks Apollo was a waste.

In late 1952 the USSR, Soviet Russia, exploded the first hydrogen bomb, America following suit in early 1953. These bombs were thousands of times more powerful than atom bombs (USA 1945, USSR 1949), but were heavy and cumbersome devices which could not be carried aloft on the small rockets which existed at that time. And so, both superpowers set about making the H-bomb smaller, without losing any energy yield, so that the rockets of the time, basically captured German V2s and their derivatives, could carry them.

Now in the few years which followed the Americans had some notable success in this, but the Soviets didn't. And so the Soviets, panicking a bit, changed tack and did Plan B - make the rockets bigger instead. After all, the relative simplicity of building a bigger metal tube with bigger fuel tanks and clusters of engines rather than single ones, was more within their technological grasp than getting into the complexities of nuclear physics to subtly change their nuclear devices.

By 1957 the Soviets had accomplished their aim, with a huge rocket they called the Vostok R7, while the Americans had smaller rockets with smaller but equally powerful bombs, and the balance of power was pretty stable.

But then an unexpected turn took place, which

is best summed up in this small hypothetical conversation:

Soviets: Hey, just a minute! Now that we've taken this path, more because of

what we couldn't do than what we could, why not remove the big heavy warhead

from the top of one of our leviathans and place a small 50 kilo satellite there

instead? That zonking thing will blast it clean off the globe!

Americans (slapping hand to forehead): Oh hey.

And that arbitrary stroke of luck, right there,

put the Soviets ahead in space by more than half a decade. And during this time they had a ball.... the first satellite into orbit, the

first probe to fly past the moon, the first to hit the moon, the first to

photograph the moon's far side, the first animals into space, the first man in

space, the first 2 man crew, the first woman in space, the first 3 man crew,

the first space walk, probes to Venus and Mars -- to say nothing of the spy

satellites with lenses 2 feet across which could accurately resolve every

square inch of American territory. Oh, what their new toys could do, when they

weren't lumbered down with heavy warheads!

But the Soviets were also doing something far more profound and sinister -- they were seducing the Third World into thinking that communism was a miraculous way of life which could spectacularly transform their nation, and making their leaders look up in awe at that tempting possibility. After all, Russia had until recently been a poor, impoverished place where people had struggled in their tens of millions, yet here they now were, only a few decades into their communist experiment, setting such impressive examples.

This developing situation was not recognized by Eisenhower, but his younger successor John F. Kennedy saw it very clearly, together with the urgent need to demonstrate, in whichever field the Soviets might use to impress, that this seduction was ill founded. In May 1961 he had been President only a few months when in response to the latest Soviet achievement -- putting the first man into space -- he called a Special Joint Session of Congress, and the speech he gave them, the "Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs," summed up the world's slumbering predicament in a nutshell:

"If we are to win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny, the dramatic achievements in space which have occurred in recent weeks should have made clear to us all, as did the Sputnik in 1957, the impact of this adventure on the minds of men everywhere, who are attempting to make a determination of which road they should take".

Well that's pretty clear! Here is Kennedy making that speech. President Kennedy Challenges NASA to Go to the Moon - YouTube

In the same speech Kennedy mentioned how American achievement in space will hold many keys to our future on Earth, that it would impress mankind, and at the end he effectively challenged the Soviets in the area of technology and expense.

The underlying situation was that if the free world fails to prove that communism is not a better way of life which can miraculously transform nations, then America will have not one but a couple of dozen Vietnams on her hands, upwards of 15 million American dead, probable bankruptcy, and a communist world of dictatorial tyranny and paranoid purges, in which good people everywhere have to live their lives in fear for themselves and their families. Picture the entire world today being like North Korea.

By contrast, Apollo as a solution was cheap at the price and the total death count would turn out to be just 3 -- three -- individuals.

And so, Apollo wasn't about space or the moon at all. It was an answer to a crisis which here in the free west might have been the undoing of us all. It was a matter not only of American national security but of the safety of the free world. It was imperative, in whatever field the Soviets chose in which to impress, that America had to follow suit and disprove their claims, especially to the developing nations. And at this point, seemingly inexplicable matters such as elected politicians spending vast sums of public money upon peril of their own careers, at once fall into place.

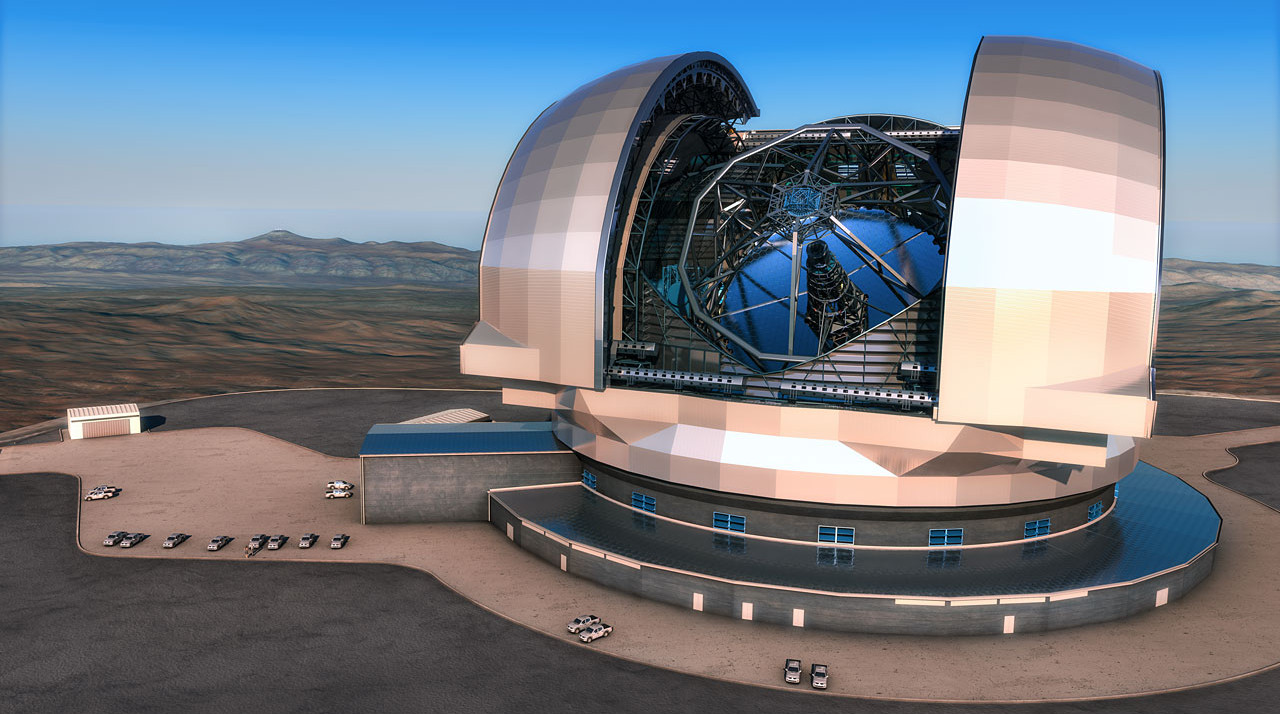

However, believe it or not, even today this urgency, wherever it arises, is still not well understood by many. The paleontologist John R. Horner once lamented that the digging up of dinosaurs was being ignored by the allocators of public funding, while the big bucks were going into the construction of huge telescopes which could see deep into the universe. But there it is again, the same factor which alarmed Kennedy 60 years ago -- national security. Quite apart from the need to identify incoming asteroids as early as possible, or to spot alien spacecraft responding to our first radio signals (now 120 light years out; they've already gone past an estimated 57,000 planetary systems containing in total over a quarter of a million planets), we also have religious fanatics consumed with hocus pocus hijacking planes full of men, women and little children, and flying them into buildings while screaming, "God is great!" In this latter case it is incumbent on us all to be able to demonstrate to our upcoming young, where the universe really did come from and where it really is going, and that hocus pocus explanations for these things are a dangerous folly.

But to impart to them that information, we must first obtain it ourselves.

Issues of national security: public investment in the prevention of future 911s.

-- Michael Alan Marshall